For five decades in a row, Citizen Kane was voted the greatest film of all time in Sight & Sound’s International Critic’s Choice poll. Although pipped to the top spot by Vertigo in the latest poll, there are still plenty of filmmakers, academics and fans who consider actor-director Orson Welles’ 1941 debut the very pinnacle of cinematic accomplishment.

The spoilt son of a hotelier and a concert pianist, Orson Welles found fame in 1938 when he directed and starred in a radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds which was so convincing that thousands thought it was real and fled their homes. Not long afterwards, RKO, one of the five big studios of Hollywood’s Golden Age, offered a generous two-picture deal to the 24-year-old who had never made a film before and didn’t much want to.

12 months and two abandoned concepts later, Welles teamed with screenplay-fixer Herman J. Mankiewicz, whose past projects included The Wizard of Oz, to script the rise and fall of a powerful newspaper magnate based on William Randolph Hearst. The pair went through five drafts, making changes for creative, financial and legal reasons (hoping to avoid a lawsuit from Hearst).

The story’s fictionalised press baron, Charles Foster Kane, dies in the opening scene, but his mysterious last word – “Rosebud” – spurs a journalist to investigate his life. The journalist’s interviews with Kane’s friends and associates lead the viewer into extended flashbacks, an innovative structure for the time.

Welles himself took the title role, spending many hours in the make-up chair to portray Kane from youth to old age. Inventive, non-union make-up artist Maurice Seiderman developed new techniques to create convincing wrinkles that would not restrict the actor’s facial expressions. Sometimes Welles would be called as early as 2:30am, holding production meetings while Seiderman worked on him.

“I was just as made-up as a young man as an old man,” Welles said later, noting that he wore a prosthetic nose, face-lifting tape and a corset to satisfy both his own vanity and the demands of the studio for a handsome leading man.

The young auteur – who directed part of the film from a wheelchair after fracturing his ankle – was not easy to work with. Editor Robert Wise said: “He could one moment be guilty of a piece of behaviour that was so outrageous it would make you want to tell him to go to Hell and walk off the picture. Before you could do it he’d come up with some idea that was so brilliant that it would literally have your mouth gaping open, so you never walked. You stayed.”

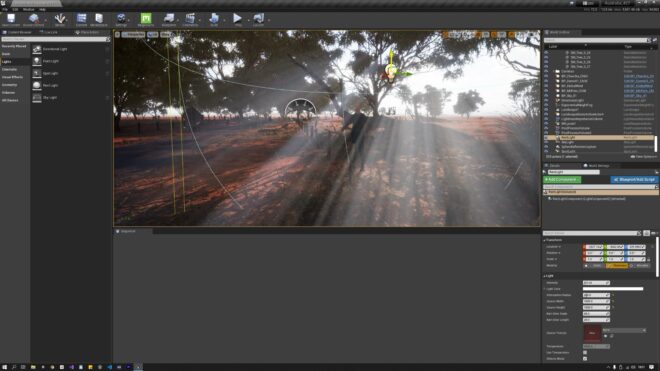

Welles was keen for his film to look different from others, drawing on his experience of directing theatre. The leading DP of the time, Gregg Toland, jumped at the chance to break the rules. Influenced by German Expressionism, he was not afraid of silhouettes and bright shafts of light.

Welles cast many of his Mercury Players – a theatre repertory company he had set up himself – who he knew could handle long takes. He insisted on a large depth of field and often shot from low angles to mimic the experience of a theatre-goer, specifically someone in the front row looking up at the cast. This required many of the sets to have ceilings, unconventionally, and these were made of fabric in some cases so that the boom mic could record through them.

Special effects were used extensively to reduce set-building costs and avoid location shooting wherever possible. One example is a crane-up from a theatre’s stage to a pair of technicians watching from the flies above; the middle part of the shot is a matte painting, bridging the two live-action set pieces. In another scene, the camera travels through a neon sign on the roof of a building and down through the skylight; the rooftop is a miniature, the sign is rigged to split apart as the camera moves through it, and a flash of lightning eases the transition into the live-action set.

“We were under schedule and under budget,” Welles proudly stated in a 1982 interview. He cheated though, because he asked the studio for ten days of camera tests, citing his inexperience behind the lens, and used those ten days to start shooting the movie!

When Citizen Kane was premiered in May 1941, William Randolph Hearst was not fooled by the script tweaks and took the title character as an unflattering portrayal of himself. While he was unable to suppress the film’s release – though not for the want of trying – a smear campaign in his publications ensured it only enjoyed moderate success and that Welles would never have the filmmaking career that such a startling debut should have sparked. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Citizen Kane received the critical acclaim which it still holds today, 81 years on.