A few weeks ago I discussed compositional techniques which we can learn from the work of JMW Turner. This time I’m looking at the use of light, and I’m broadening the scope to cover a few other classical artists whose works have caught my eye at galleries lately.

Without artificial illumination, these old masters had to make the most of the light God gave them. Here are five examples of their techniques which we can trace directly forward to cinematographic techniques of today.

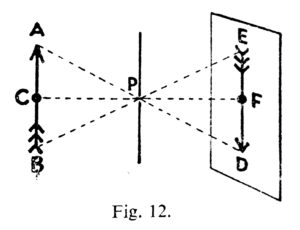

Cross-light

Decades before DPs started encouraging directors to shoot interior scenes towards windows to achieve the most interesting modelling, Sickert had the same idea. See how the light from the window in the background throws the model’s body into relief, giving it form and dimension? Cross-light is commonly used today in commercials for sport and fitness products, to emphasise muscle tone.

See also: Lighting Techniques #6: Cross-light

Background strokes

What caught my eye about this painting was the slash of light on the background wall in the top left corner. It may seem trivial, but a little stroke of background light like this can really elevate the quality of a shot. Here it anchors the corner of the composition and gives us a hint of the room’s decor, adding interest to what would otherwise be a black void behind Guismond.

While lighting the subject of the shot is clearly a DP’s priority, it’s important to find time to paint in the surroundings even if they’re in the deep background or extreme foreground.

See also: 5 Ways to Use Hard Light Through a Window

Haze

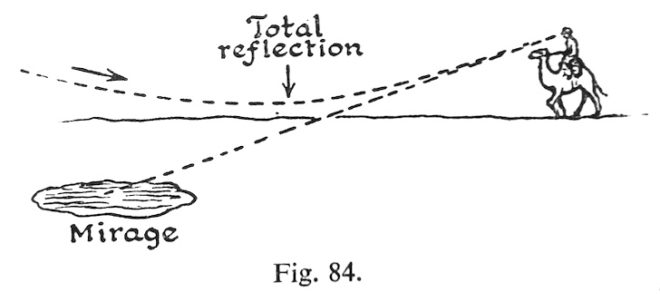

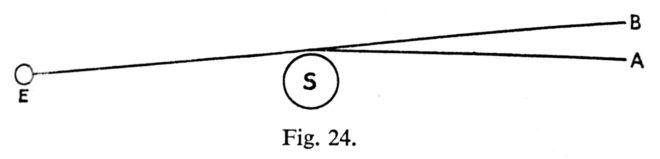

This monochrome etching has a tremendous feeling of depth, and it is achieved purely through contrast. The further away an object is, the more air there is between that object and your eye. Since air isn’t 100% transparent, that distant object appears lighter and lower-contrast than closer objects. Gessner and Kolbe capture this effect beautifully here.

Many cinematographers today use hazers to create or enhance this atmospheric effect, even for interiors. In the days of miniature effects, smoke was often used to create atmospheric haze and increase the feeling of scale. On Blade Runner, for example, Douglas Trumbull’s VFX crew sealed the motion control stage and used infra-red sensors linked to hazers to automatically keep the smoke level constant during the long-exposure passes over the futuristic cityscape.

See also: Depth Cues in Cinematography

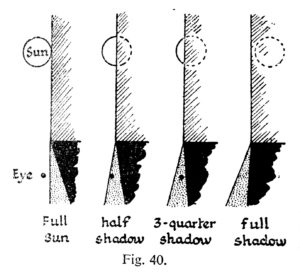

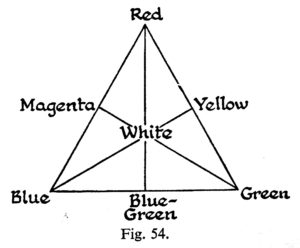

Golden hour

Painters figured out centuries ago that the most beautiful light is found at the beginning and end of the day. It’s partly due to the cross-light effect (see above) of the lower sun, and partly due to the beautiful orange colour caused by the greater amount of atmosphere the sun’s rays must pass through. To shoot the perfect sunset, you’ll need patience, and a sun-tracker app or at least a compass. Ensure the schedule permits you to try again another day if clouds spoil the view.

See also: Sun Paths

Wet-Downs

This is the only night image in a series of impressionist oil paintings which Pissarro executed from a hotel window overlooking the Boulevard Montmartre. What makes it particularly beautiful is the wet street, turning what might otherwise have been a dull grey central swathe of the image into an arena of alternately shadowy and glittering reflections.

Cinematographers shooting night exteriors on streets will often have the tarmac hosed down for four reasons: (1) as already noted, the beauty of the reflections; (2) the deeper blacks and increased contrast; (3) the extra exposure gained by the light sources bouncing off the water; and (4) avoidance of continuity problems if it rains.

See also: 7 Considerations for Night Shooting

I joined this social media platform last summer, after hearing DP Ed Moore say in

I joined this social media platform last summer, after hearing DP Ed Moore say in