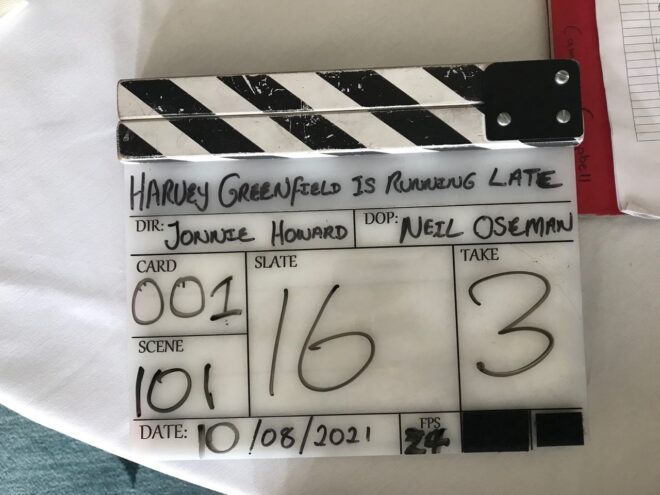

Day 17

Our first location was a medical training ward populated by creepy dummies; we had a brief flashback scene to do around a hospital bed. When we arrived there was nice warm sunlight coming in through the frosted glass behind the bed, so we made sure that stuck around by putting an orange-gelled Aputure 600D out there. Inside we wrapped this with a FalconEyes and Stephen added some soft fill because I wanted the scene to feel romantic. To get some green into the frame (a calming colour in the film’s visual language) we stuck a couple of Nanlite PavoTubes into the background as practicals.

While Hamish (our new 1st AC) and Fifi were building the camera I faffed about with the Prosup Tango slider, trying to figure out a way to have the track go over the bed so we could pull straight back from Paul. It proved impossible simply because the track also ended up in frame, and instead we simply set it up beside the bed. It took a bit of clever blocking by director Jonnie to ensure that the camera could point directly along the axis of the track, rather than at an angle, which would have broken the established visual grammar of the film. This is the sort of thing that takes a bit of time to get back into after months away from the project, but it’s important to get it right.

Next we moved into the foyer, which we were playing as a bank. There was plenty of natural light but we made sure to keep that in the background, neg-filling behind the camera, and adding a key (a Rayzr MC 200) at 90° to the talent (Alex Wilber), who was partly facing towards a computer monitor on that side of camera anyway. A heavily dimmed 2K served as backlight.

After a brief panic when we thought we were missing our favourite lens, the 14mm, we moved to Cambridge 105’s studio a couple of blocks away. A special guest star played a Tony Blackburn-esque DJ and threw in some brilliant improvs.

We fought a battle against the high, bright sun that kept trying to come in the south-facing window, despite us having diffed a lot of it, and blacked out the whole top section, and having blinds partly lowered, and the windows having some special solar coating on them anyway. Once again we fired in the 600D, which probably did very little compared with that sun, and wrapped it inside with a FalconEyes, and added the PavoTubes into the background for colour. The DJ’s computer monitors were set to 60Hz, but I’d learnt my lesson from last year and immediately set the shutter to 144° to sort that out.

Day 18

We were at Anglia Ruskin University for the day, mostly in one of their media studios. Here we had to shoot a number of things against a black backdrop, mainly to cut into the climax of the film. These included a 180° camera move using the university’s track and dolly. I thought briefly about doing some elaborate lighting rig in which lamps would have to be dimmed up and down to maintain backlight and eliminate front-light as the camera circled, but then I came to my senses and we just fired a Source Four straight down onto the makeshift table that the two actors were hunched over so that it would bounce back up to them. I was using the Soft FX 1 to match the look of the Happy Place scenes from Day 3, which helped to take the harshness out of the highlights where the Source Four was directly hitting the cast.

A little later Jonnie started flinging things in front of the camera. Had he finally cracked? No, he just wanted some lovely slo-mo shots of key props arcing through a black void. We went to 120fps, the Red Gemini’s maximum 4K frame rate, and the higher native ISO of 3200. We were able to make a stop of somewhere between T4 and T5.6 by bouncing two 2Ks into an 8×4′ poly just out of frame, and using three triple banks of the uni’s linear cyc lights in the grid as backlight.

After lunch we came to a couple of crucial shots that were dropped from the night shoot on Day 10, meaning we had to replicate the lighting from Vinery Park. We used the cycs again, a Source Four on a stand as a special flaring backlight simulating the park’s streetlamp, and a couple of 2Ks through a diffusion frame as the key. Although we were back to 24fps we still needed loads of light because one of the set-ups was on an f/14 probe lens sliding into Harvey’s mouth! “It feels really weird,” Paul remarked. Yep. And sorry for bashing you in the teeth with it.

As our time on the campus ticked down we moved across to another building to shoot a call centre scene. We went for our 24mm “tableau” frame that we’ve used to establish all the characters who ring Harvey in their own environments, followed by a couple of other set-ups. We kept the talent’s (Kate Madison) eye-line between the camera and the windows for a nice short key, beefing it up with a FalconEyes, and added a dimmed 2K backlight and some warm PavoTubes in the background (orange being the stress colour in the film’s visual language).

Day 19

The good folks at BBC Breakfast were up bright and early, set up at the Granta beside Sheep’s Green, shooting live news footage of what was widely forecast to be a record-breakingly hot day. We were up pretty early too, watching from the banks of the Cam at 5:30am as the BBC drone flew over, and hoping that it wouldn’t ruin a take (which it didn’t).

We were shooting Harvey Greenfield‘s only stunt, which I probably shouldn’t spoil by describing. We’d given Stephen the day off, and my trusty 5-in-1 reflector was our only lighting gear, but of course there was no shortage of sunlight. I used the white side for most set-ups, running along beside the Steadicam later in the day to keep Paul’s face filled in when he wasn’t facing the sun.

There was an interesting moment when we had the sun in the background of a low-angle shot. As I’ve experienced before, the Soft FX filter reflected a rectangle of light onto the subject. But even when we took it out, the IRND filter did the same thing. Do all filters do it, I wonder? Must test that one day.

We wrapped a little after 3pm, as the heat was reaching its maximum. Despite all the dire warnings (and drone-worthy news coverage) it hadn’t been too hot to work. We were all sensible with hydration, shade and sunblock, and I even swam in the Cam a couple of times during the day to cool off. You don’t get to do that very often on a shoot!

Straight after wrap I went for another swim in Jesus Green Lido, whence a Channel 5 news crew were broadcasting live weather reports with the pool in the background. The presenter was positioned in the shade and they’d set up a 600D on either side of him to fill him in. Believe it or not, that would inspire the next day’s lighting.

Day 20

First up was a one-shot flashback scene at the Arts Picturehouse. We used the 600D as the “projector”, positioning it just barely out of the top of frame, and a 4×4′ poly armed over the camera as the screen bounce. During the takes Jeremy wiggled his hand in front of the 600D to create dynamics in the flare.

The day’s main scene was a fake advert starring a nineties keep-fit icon. The aim was a cheesy infomercial vibe, with a 4:3 aspect ratio and over-the-top acting. We cross-front-lit the scene with the Aputures 300D and 200X (thank you, Channel 5), with only a bit of diff on them. I over-exposed by a stop and took out the Soft FX filter to make the image even less filmic. I framed with a lot of headroom and even did a deliberately late tilt-down at one point. When the actual aerobics start, we went even more naff by adding two PavoTubes into the background and the Rayzr MC behind camera, all flashing nasty disco colours. It was great fun.

By the time we moved onto the last scene – another 24mm phone call, in a GP’s waiting room – it was at least 39°C in Cambridge and the UK’s temperature record had been broken.

There’ll be more from this shoot in next week’s post. In the meantime, you can read all the Harvey posts here. Note that the link will display them in reverse chronological order, so scroll down for the older ones.