Although The Little Mermaid takes place mostly on dry land, there were some key scenes involving tanks and pools. These include the moment which introduces the audience to the mermaid herself, played by Poppy Drayton. Here are some extracts from my diary covering the challenges of creating a magical, fairytale look while filming in and around water.

Day 10

Today we’re inside the big top all day – actually all NIGHT. We can’t shoot during the day because too much daylight bleeds through the canvas of the tent.

We are setting up when a storm hits. The tent starts to blow about in a slightly alarming fashion, rain lashes down outside (and inside, because the tent isn’t very waterproof) and lightning flashes. We are ordered out of the tent, and I run into a waiting mini-van with Joe from art and some of the camera crew. We sit watching the rain and telling stories for half an hour before we can press on.

Around the wall of the tent the art department have hung canvas posters; at the suggestion of gaffer Mike Horton, we uplight these with par cans and par 38s. The design of these fixtures hasn’t changed since the 30s, so we can get away with seeing them in shot. The art dept have sourced four period spotlights which we use as background interest (they’re not powerful enough to really illuminate anything), as well as string-lights.

Ambience comes from a Maxi Brute, with just a couple of bubbles on, firing into the tent roof. After seeing a video test of various diffusers during preproduction, I asked for Moroccan Frost to be added to our consumables list, and we use it for the first time on this Maxi Brute. It gives a lovely muted orangey-pink look to the scene.

We’re shooting our mermaid for the very first time, in a tank in the circus ring. The initial plan is to fire a Source Four straight down into the water to create genuine watery rippling light, while bouncing a par can off a wobbling frame of blue gel to beef up the effect. In the end the Source Four isn’t really cutting it, so instead we rig a 575W HMI, gelled with Steel Blue, to a menace arm and fire it into the tank as toppy backlight. This Steel Blue gelled daylight source, blued up slightly further by the water itself, contrasts beautifully with the Moroccan Frost tungsten ambience which the Maxi Brutes are giving us.

In her mermaid tail and costume, Poppy Drayton looks stunning in the tank. We shoot steadicam angles and some slo-mo to get the most out of the set-up.

Day 15

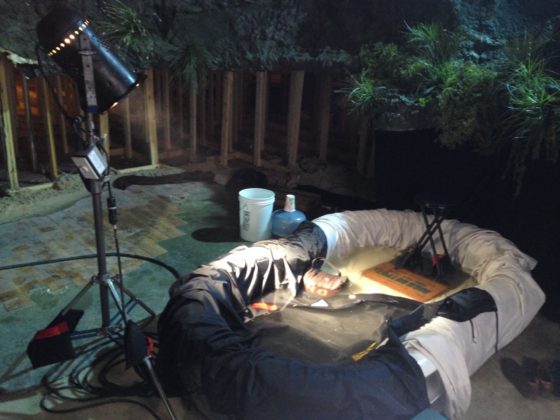

Back on stage, and we’re shooting the rocky pool. This set was built before I even arrived in Savannah, so I’ve been waiting a long time to shoot it. It’s built almost right up to the ceiling of the studio (a former supermarket) so it’s challenging to light. The grips build four menace arms and poke two 4×4 Kinos and two 575W HMIs over the sides to cross-light the set and bring out all the texture in it. Where the set ends they put up a 20×20′ greenscreen, which we light with two Kino Flo Image 80s fitted with special chroma green tubes.

After a wide (which didn’t make the final cut), the next set-up is a 2-shot of our leads in the pool itself. We consider arming the camera out over the pool using a jib, but ultimately decide that it’s better for me to join the cast in the pool, with the camera on my shoulder in a splash bag. 2nd AC Kane Pearson joins the pool party as well, and ends up hand-bashing a monitor for me since the splash bag’s designed for a Panaflex film camera and the viewfinder doesn’t line up. I’m reminded of my frustrating splash bag experience on See Saw back in 2007, but this time at least within a few minutes I’ve found a comfortable and effective way to operate the camera, under-slinging it and allowing it to partially float so I don’t have to support the whole weight.

After a wide (which didn’t make the final cut), the next set-up is a 2-shot of our leads in the pool itself. We consider arming the camera out over the pool using a jib, but ultimately decide that it’s better for me to join the cast in the pool, with the camera on my shoulder in a splash bag. 2nd AC Kane Pearson joins the pool party as well, and ends up hand-bashing a monitor for me since the splash bag’s designed for a Panaflex film camera and the viewfinder doesn’t line up. I’m reminded of my frustrating splash bag experience on See Saw back in 2007, but this time at least within a few minutes I’ve found a comfortable and effective way to operate the camera, under-slinging it and allowing it to partially float so I don’t have to support the whole weight.

For this shot we’ve added our par-can-bounced-off-a-wobbling-blue-gel gag for watery light ripples, and combined with the real light ripples and the reflections of a 1.2K HMI backlight, the image looks beautiful.

Day 19

After lunch we shoot the singles for the rocky pool scene. The pool itself has been removed, and the actors sit on stools in a paddling pool, with the set behind them. The paddling pool serves two functions: it catches the water that make-up pours over the actors to make them look wet, and it reflects rippling light onto their faces. This light originates from a par can. At first it flattens out the look, then we figure out that we need to lay black fabric on the bottom of the pool. This stops the par can’s light bouncing directly, while retaining the rippling highlights off the water’s surface. (Check out my article on shooting water for more tips like this.)

In the final edit this was all intercut with some beautiful footage by underwater DP Jordan Klein, shot both at a local diving pool in Savannah and at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park in Florida. The main unit shot another scene in the actual ocean, but I’ll cover that later in this series. In the meantime, next week I’ll reveal some of the tricks and techniques used in shooting The Little Mermaid‘s many sequences in moving vehicles.