This week I attended Camerimage for the first time. Centred around the Opera Nova theatre beside the river Brda in Bydgoszcz, Poland, Camerimage is an international film festival celebrating the art of cinematography. It’s a bit like Cannes for DPs, but colder. This is the first part of my account of my three days at the annual hub of motion picture imaging.

This week I attended Camerimage for the first time. Centred around the Opera Nova theatre beside the river Brda in Bydgoszcz, Poland, Camerimage is an international film festival celebrating the art of cinematography. It’s a bit like Cannes for DPs, but colder. This is the first part of my account of my three days at the annual hub of motion picture imaging.

The Ryanair flight was dirt cheap but trouble free, and at 9:50am I found myself on the tarmac of Bydgoszcz airport. There I met David Shapton and Matt Gregory, founders of Red Shark News, for the first time. I’ve been contributing articles to Red Shark for a few months so it was nice to finally meet these gentlemen in person.

A taxi (also dirt cheap) dropped me at the Opera Nova – only about three miles from the airport – where I picked up my pass and goodie bag. Bizarrely, said goodies included an Ikea catalogue. How did they know that us DPs love flat-pack furniture so much?

Canon Workshop: Stephen Goldblatt

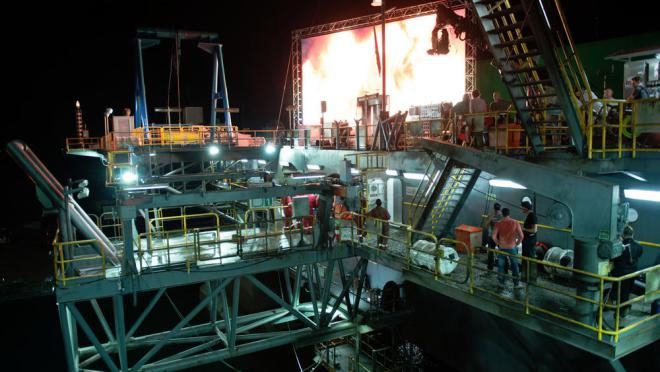

From the Opera Nova I hurried to a college across the river, where the sports hall formed the venue for a Canon workshop run by Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC, the man behind the lens for the likes of Lethal Weapon 2 and Batman Forever. The blurb for this workshop described Goldblatt as “a master of low light shooting”, and it was certainly pitch black when I walked in a few minutes late, and gingerly picked my way around to the far side of the hall to find a seat.

On a purpose-built bedroom set, Goldblatt was recreating lighting from the Robert Redford / Jane Fonda romantic drama Our Souls at Night, shot on the Sony F55 and Canon C300 Mark II. To practical lamps on either side of the bed he added egg-crated tungsten soft-boxes to beef up each one. He simulated moonlight through an imagined off-camera window by placing a lace curtain in front of a blue-gelled lamp and blowing it gently with a fan. An additional egg-crated soft-box provided a low level of blue toplight.

As he worked, Goldblatt revealed how he doesn’t miss ceulloid, loving how relatively easy it is now to light night exteriors or moving car scenes. “But just because you don’t need much light,” he cautioned, “it doesn’t mean you don’t want to control it.” Other developments coming down the pipe do not inspire him so much; he feels that high resolutions and HDR are unnecessary, pushed by marketing people rather than creatives.

He placed great emphasis on the importance of the eyes. “A common failing of newer DPs is that they worry more about the set than the eyes,” he said, before explaining how he will often walk beside the handheld camera with a torch, providing eye-light. He also stressed the importance of eye-lines. Although in any one shot it’s not that important how wide or tight the eye-line is, or how high or low, across the two hours of a feature film the decisions have a cumulative effect.

Goldblatt no longer uses a light meter. “Trust your eye, develop your eye,” he advised, adding that you must have a strong voice to remain in control of the images through postproduction.

After grabbing lunch, I returned to the Opera Nova to browse the exhibition hall. This closely resembled a mini BSC Expo or Media Production Show, with all the major camera and lens manufacturers displaying their wares, along with several lighting companies. I had a play with some of the cameras, including the actual Alexa 65 used on Rogue One.

Then I met up with Chris Bouchard, one of The Little Mermaid‘s two directors, who had arrived in Poland the previous day. We sauntered over to another venue, the MCK Orzeł, an independent cinema with a nice, chilled, film-buff-friendly atmosphere. The auditorium itself was packed though as we settled in for a seminar on “The Future of Digital Formats”.

Red Seminar: The Future of Digital Formats

Promoting Red’s Monstro sensor, the session was mostly about the benefits of shooting in high resolutions, and giving yourself the maximum flexibility in post. You can read my thoughts on both of those topics in upcoming Red Shark articles.

One of the speakers, Christopher Probst, ASC (DP of Mindhunter and technical editor of American Cinematographer magazine) made some interesting points about ISO. “Traditionally, low ISOs were used for bright scenes like day exteriors, and high ISOs were used for darker scenes like night exteriors,” he explained. “That was based on reducing the grain, getting the cleanest possible image on film.” He advised the opposite for digital capture. “Use a low ISO for nights to get more shadow detail, and a high ISO for days to get more highlight detail [in the sky, for example].”

Another interesting nugget came from Markus Förderer, BVK. On Independence Day: Resurgence he switched between spherical, 1.3x anamorphic and 2x anamorphic lenses depending on the situation. For example, flatter lenses were better for wide shots – where anamorphics would distort straight lines – and for VFX work.

Hawk Vantage Seminar: Top cinematographers tell their Hawk stories

I ducked out of the Red session early so that I could pop back to the Opera Nova for the Hawk Vantage seminar, bumping into my Perplexed Music gaffer Sam Meyer on the way. Hawk were launching three new sets of lenses: MiniHawk (T1.7 hybrid anamorphics), Hawk Class-X (T2.2 2x anamorphics) and Hawk65 (T2.2).

The MiniHawks in particular seem very exciting. Daniel Pearl, ASC showed us some stunning frame grabs from the upcoming Dennis Quaid vehicle Motivated Seller, shot using these lenses on Alexa Mini. Whilst having key advantages of spherical lenses (speed, small size, low weight, extremely close focus) the MiniHawks have a unique and beautiful cigar-shaped bokeh.

While Pearl had used the latest Hawks, Magdalena Górka, PSC had shot with some old ones, the C series, for Brad Silberling’s drama An Ordinary Man. “I had to frame everything centrally because that’s the only place that was sharp!” she laughed. Also addressing focus fall-off, Andrzej Bartkowiak, ASC (Speed, The Devil’s Advocate) stated, “I like anamorphic because the shallow depth of field allows you to direct the viewer’s eye more.”

Stuart Dryburgh, ASC (The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Bridget Jones’s Diary) talked about shooting 1.3x anamorphic. He has done this on three-perf 35mm (to achieve a Scope aspect ratio), on an Alexa in 16:9 mode (again for 2.39:1) and on an Alexa in 4:3 mode (to get 1.85:1). He also recommended shooting on Super-16 with 1.3x glass, citing the example of Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud” video, which Pearl shot.

Peter Flinckenberg, FCK (Upswing, Concrete Night) noted that, with the shift to digital acquisition, the DP is no longer a magician, “but you can bring back that magic with lighting and glass that has character.”

CW Sonderoptic: Exploring Large format cinematography & Leica lenses

I took my leave, dashing back to the MCK Orzeł for another lens-themed seminar, this time by CWSonderoptic, the makers of Leica. The first half of this panel revolved around a short film shot by Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC (Seven, Delicatessen) on an Alexa 65 with the new Leica Thalias.

The second half was all about Tod Campbell, DP of Stranger Things and Mr. Robot, focusing on the latter show. The second season of Mr. Robot was shot on Leica Summicrons after Campbell found that the Cookes used on season one distorted the many straight lines which became such a key part of the show’s unique look. “I look at season two as kind of the birth of the photography for the show,” he said. With a laugh he added: “Sorry that the lighting looks like shit in season one. I was learning!” (See my spherical lens tests for my own thoughts on Cookes and Leicas.)

Campbell revealed that season three of Mr. Robot has a different look again, using much more camera movement and “twice as much atmos”. For this season he paired Canon K35 glass with an 8K camera, but due to the Canons’ low resolution he employed Leica Summiluxes for the wide shots.

He also shared some interesting information about his testing process, admitting that he doesn’t really know how other DPs test. He doesn’t use charts, he just makes it up. He always includes a candle, a practical lamp, some kind of highlight in the background, and random foreground objects (as background bokeh can differ from foreground bokeh).

Christopher Doyle Seminar

When the Leica seminar ended I went back to the Opera Nova, where Chris and I had dinner at the nice (and once again cheap – are you detecting a theme?) restaurant. Despite having got up at 4am (3am local time) I wasn’t feeling too tired, so we headed upstairs to the 10pm seminar by Christopher Doyle, HKSC (Hero, Lady in the Water). Many people were nursing beers, including Doyle himself, and the lecture theatre was dimly illuminated by mood lighting. Clearly this session was not going to be like the daytime ones.

“We’re going to fuck things up,” Doyle began, dispelling all doubts. He proceeded to talk disjointedly but entertainingly about his work on The White Girl and what I think was a separate film about a camera obscura. His oratory was liberally sprinkled with great one-liners, a few of which I reproduce here for your edification:

- There are only three people in filmmaking: the actor, the audience and the cinematographer in between them.

- If actors don’t feel loved, the performance will not come across on camera.

- Give the idea the image it deserves.

- [Vittorio] Storaro [legendary DP of Apocalypse Now amongst others] can’t tell you how to do it. You have to find it for yourself.

- People in space – that’s what cinematography’s about.

- The location is very important. It gives the energy, it imposes the style.

- The lens doesn’t matter; it’s what it shows that’s important.

- You never sleep because you care too much – that’s what filmmaking is.

Doyle also picked up on a piece of dialogue from a clip he screened: “What is it?” / “I don’t know yet.” It was a great summation of finding the essence of a shot, he said.

Having had our fill of aphorisms, Chris Bouchard and I slipped out to get a drink. The Cheat, the pop-up bar across the road, was absolutely packed, and my early morning was finally catching up with me, so I called it a night. The highstreet of Bydgoszcz was quiet and chilly as I walked briskly to my hotel, curiously located down a service road behind the city’s football stadium, reflecting on all that I had learnt that day.

Tune in next week for tales from my second day at Camerimage.