I’ll soon be starting five weeks of prep for a feature, and it’s got me thinking about the five weeks I spent in the spring of 2016 prepping The Little Mermaid. I published a number of entries from my production diary when the film was released, but the entries from pre-production have gone unseen… until now…

JANuary 12th, 2016

It is four or five months since Chris, the director, first mentioned the project to me. In that time he has been developing the script with the writer and producers, and I’ve read a draft or two. Last week I was introduced to the producers by email, and today Chris and I get together to start chatting about the film.

It’s just broad strokes today, nothing structured, nothing firm. He talks me through the next round of script changes and we watch some bits of DVDs I’ve brought. I’m not thinking photographically yet, just tone and genre, so we watch parts of The Rocketeer and Big Fish. I start to get some basic ideas of what Chris does and doesn’t like.

Yesterday I went to the library to get my head around the geography of the state our story is set in, and bit of the history and culture. I found a book called Photographing America and it has some interesting plates from the Deep South in the 30s and 40s. They set the stage for me in terms of architecture, landscape and clothing, but their gritty black and white photography is not appropriate for this film.

Chris and I Skype Fabio, the line producer, and later have a brief conference call with producers Armando and Rob. At this stage it is just about introductions. Chris enthuses about me to them, and curates some stills from Ren: The Girl with the Mark to wow them with. Armando responds positively – it’s just the look he’s after for this. Well, this is the second feature job Ren’s got me. Cheers, Kate!

Week 1

Since that day in London with Chris, I’ve done bits and pieces of prep around finishing up post on Ren. The script went through a few more drafts, I joined in a few conference calls with members of the team, and started a shot list.

But on March 5th I fly into Savannah, Georgia and I’m straight into full-time prep, living and breathing A Little Mermaid.

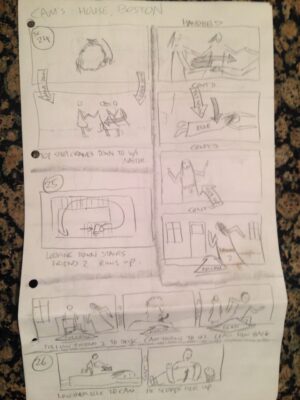

On Sunday I wake early, my body still five hours ahead of US East Coast Time. After talking to Chris, who’s still in the UK due to visa delays, I take a ten-minute walk through the sunny streets of Savannah to meet David, the storyboard artist. We eat blueberry pancakes with maple syrup and he shows me his boards for the movie’s finale. Chris Skypes in and we discuss the priorities. We need about 15 more sequences boarded – at least key frames – ASAP so that production designer Jay can be sure to accommodate our needs in the sets he is already starting to build.

At noon I head over to an apartment complex where Jay and line producer Fabio are staying. This place has a pool so I’m getting myself moved here as soon as I can. We spend seven or eight hours, with Chris on Skype, going through the schedule line by line, making sure everything is doable and everything is in the most efficient order.

Poppy Drayton is playing our mermaid. Back at the apartment I watch a trailer for The Shannara Chronicles and screen-capture all her close-ups. I analyse the lighting in each one, labelling them accordingly in a folder. Her time on this production is limited so I probably won’t get to camera-test her; I need to figure out how to light her based on what other DPs have done.

Monday is my first day at the warehouse. It’s an old supermarket that’s been gutted. There are four or five small offices and then a huge open space, part of which is occupied by the bones of the “rocky pool” set.

The week soon settles into a blur of video calls with Chris, interviews with potential camera assistants and gaffers, and lots of discussions about sets and locations. It’s really exciting to be shown around the space by Jay as he describes all the sets he’s going to build. For some scenes there is a lot of back and forth about whether they should be studio or location. We are working with a child actress and Chris is very keen to get the best performances, so the level of control we could get in the studio is very appealing, but that must be balanced against our art department budget.

I’m assigned an office that’s just 6ft square but is very cool because it has a sort of camera obscura in the door so I can see a little projection of what’s outside. Of course the door doesn’t really close properly (particularly once I’ve run an extension cable in to compensate for the lack of functioning power sockets in the room) but never mind. By mid-week I have a monitor to hook my Mac Mini up to and I’m properly in business.

I task the PAs with printing out the script and taping it in a long line of pages along a wall along with the corresponding storyboards. Eventually we will add reference images and concept art, if I can ever get access to a functioning colour printer!

A little bit of location scouting takes place during the week. We check out a nice rustic field behind the studio where we’ll set up our circus, we visit a fort in the hope that it might work for a scene near the finale (it doesn’t) and I take a look around the beach house we’ll be shooting the film’s present-day book-ends in on March 20th and 21st. (Principal photography starts April 11th.)

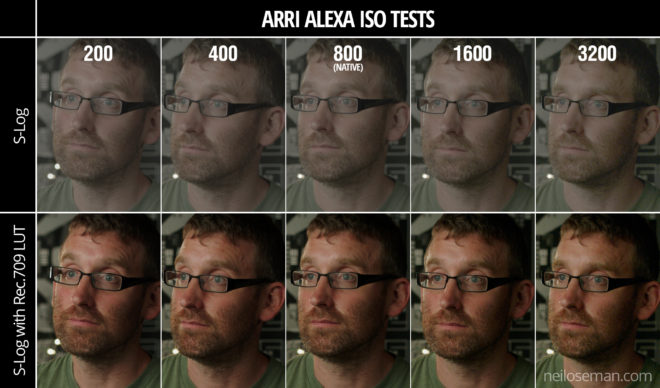

Another issue to be decided is which camera to shoot on. Initially we discussed having lots of cameras, which meant going with Reds for budgetary reasons. The Panasonic Varicam is suggested, and I’m almost flown to Atlanta to test it, but in the end we decide to go with Alexas, thank God. (With hindsight, I really should have gone and tested that Varicam. I was irrationally against all non-Alexa cameras at this time.) We’ll have two bodies, one for me and one for a B camera operator who will sometimes splinter off into a 2nd unit. The glass will be Cooke S4s with a half Soft FX filter, the exact same recipe as Heretiks. I know this will give me the organic, period feel that A Little Mermaid needs, as well as the magical quality. We’ll also have a couple of Optimo zooms in the kit, a luxury we couldn’t afford on Heretiks.

By the end of the week I’ve pretty much locked down the camera kit, finished the shot list for the whole movie, and hired 1st and 2nd ACs and a 2nd Unit DP. We still don’t have a gaffer, which is worrying. The crew pool in Savannah is not huge and we’re struggling to find people with enough experience.

On Saturday, aside from a couple of hours in the studio, I chill out. I’ve now moved to the same apartment complex as the rest of the crew, and I’ve just had a very nice dip in the pool. I think I might just have the best job in the world.

Week 2

At the end of this week we have our two-day “pre-shoot” with Shirley MacLaine, to capture the contemporary bookends to what is otherwise a 1930s story. Peter Falk’s scenes in The Princess Bride are an inevitable reference for these.

Director Chris is still having visa issues, so writer Blake will be on helming duty for the pre-shoot. He gives me Maggie Smith’s storytelling scene in Hook as a reference. I haven’t seen the movie in ages, so I rent it and watch the whole thing, delighting in the beautiful cinematography. I love the candy blues and hot pinks of Wendy’s London home, and will aim to emulate them.

A lot of this week is taken up with locking down equipment and personnel for the pre-shoot. The biggest issue as the week opens is that I still don’t have a gaffer. With my options limited – and despite a brief panic during which flying my UK gaffer out here seems like a very real possibility – I pick someone on a trial basis. If they do a good job for the pre-shoot they’ll get hired for principal.

Because the gaffer is hired so late, putting together a lighting list is my responsibility. I hate doing this, because I always forget stuff and piss everyone off at the last minute by making additions or changes. Like forgetting to check whether the HMIs are pars or fresnels. (I always want fresnels because they produce better shafts of light.)

With equipment and crew in place, my attention turns towards principal for a little while. The VFX supervisor, Rich, has flown in from LA, and together we scout some locations. Unfortunately none of the locations are locked yet and the options we are given to look at are far from ideal. But we have a good session going through the shot list together, checking that there aren’t any VFX requirements that he missed in his breakdown.

We also discuss shooting format, which is generally going to be 2K ProRes 4444. He wants me to shoot green-screen shots in Arri Raw, but after he’s gone I realise that we don’t have the right Codex on our cameras for that. 3.2K ProRes will have to do. Another good tip Rich gave me is to expose the green-screen at key (i.e. the same light reading on the green-screen as on the talent’s face) or up to half a stop over.

I’m glad I invested in a light meter, which arrived at the studio this week. It also comes in handy during another scout of the pre-shoot location. We have some night shots on the beach, which will have to be shot at dusk because it’s too big an area to light artificially. During the scout I take light readings on the beach at dusk, and determine that we have until 7:50pm, 20 minutes after sunset, before it is too dark to shoot.

If you want to follow the chronology, my diary entries about the “pre-shoot” are here.

Tune in next week for my diary entries from the remaining three weeks of prep. The Little Mermaid is still on Netflix if you fancy checking it out.

The few of us that were left then regrouped at Jonnie’s house for some ADR and a handful of inserts. The probe lens got another airing to capture a macro shot of a tape recorder, and I got to double as Harvey’s hands flicking through a book. In Paul’s very last shot he was out of focus, due to a lack of continuity-matching make-up, with the book sharp in the foreground.

The few of us that were left then regrouped at Jonnie’s house for some ADR and a handful of inserts. The probe lens got another airing to capture a macro shot of a tape recorder, and I got to double as Harvey’s hands flicking through a book. In Paul’s very last shot he was out of focus, due to a lack of continuity-matching make-up, with the book sharp in the foreground.