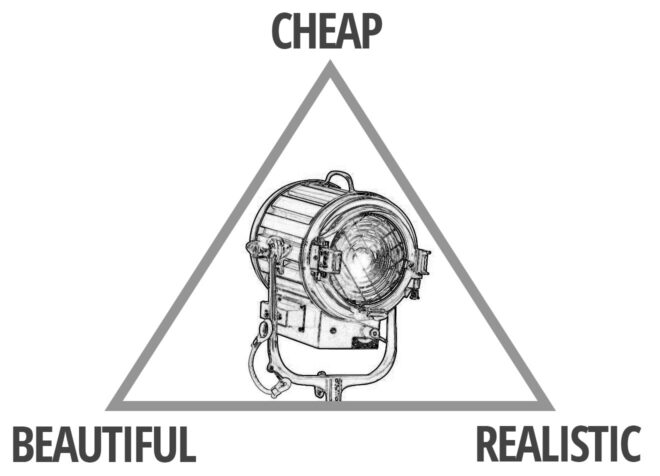

We’re all familiar with the “good/fast/cheap” triangle. You can pick any two, but never all three. When it comes to lighting films, I would posit that there is a slightly different triangle of truth labelled “beautiful/realistic/cheap”. When you’re working to a tight budget, a DP often has to choose between beautiful or realistic lighting, where a better-funded cinematographer can have both.

We’re all familiar with the “good/fast/cheap” triangle. You can pick any two, but never all three. When it comes to lighting films, I would posit that there is a slightly different triangle of truth labelled “beautiful/realistic/cheap”. When you’re working to a tight budget, a DP often has to choose between beautiful or realistic lighting, where a better-funded cinematographer can have both.

I first started thinking about this in 2018 when I shot Annabel Lee. Specifically it was when we were shooting a scene from this short period drama – directed by Amy Coop – in a church. Our equipment package was on the larger side for a short, but still far from ideal for lighting up a building of that size. Our biggest instrument was a Nine-light Maxi Brute, which is a grid of 1KW par globes, then we had a couple of 2.5K HMIs and nothing else of any signifcant power.

The master shot for the scene was a side-on dolly move parallel to the central aisle, with three large stained-glass windows visible in the background. My choices were either to put a Maxi Brute or an HMI outside each window, to use only natural light, or to key the scene from somewhere inside the building. The first option was beautiful but not realistic, as I shall explain, the second option would have been realistic but not beautiful (and probably under-exposed) and the third would have been neither.

I went with the hard source outside of each window. I could not diffuse or bounce the light because that would have reduced the intensity to pretty much nothing. (Stained-glass windows don’t transmit a lot of light through them.) For the same reason, the lamps had to be pretty close to the glass.

The result is that, during this dolly shot, each of the three lamps is visible at one time or another. You can’t tell they’re lamps – the blown-out panes of glass disguise them – but the fact that there are three of them rather gives away that they are not the sun! (There is also the issue that contiguous scenes outside the church have overcast light, but that is a discontinuity I have noticed in many other films and series.)

I voiced my concerns to Amy at the time – trying to shirk responsibility, I suppose! Fortunately she found it beautiful enough to let the realism slide.

But I couldn’t help thinking that, with a larger budget and thus larger instruments, I could have had both beauty and realism. If I had had three 18K HMIs, for example, plus the pre-rig time to put them on condors or scaffolding towers, they could all have been high enough and far enough back from the windows that they wouldn’t have been seen. I would still have got the same angle of light and the nice shafts in the smoke, but they would have passed much more convincingly as a single sun source. Hell, if I’d had the budget for a 100KW SoftSun then I really could have done it with one source!

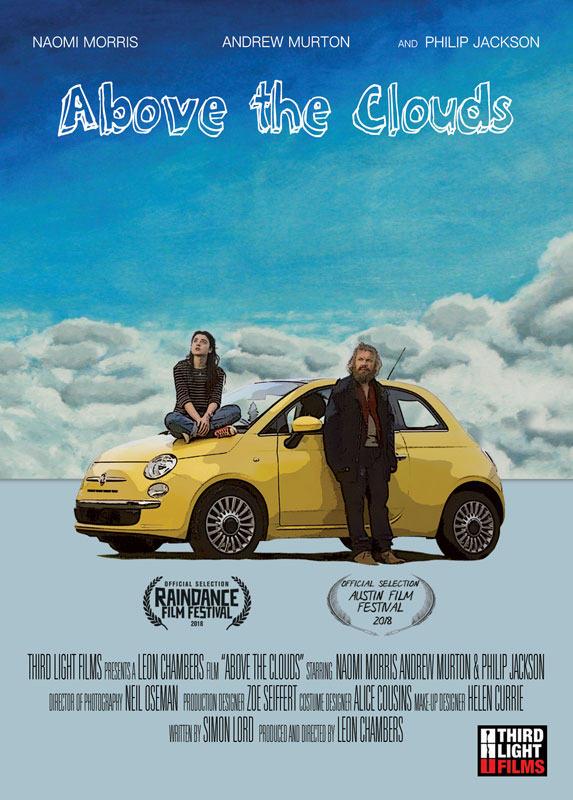

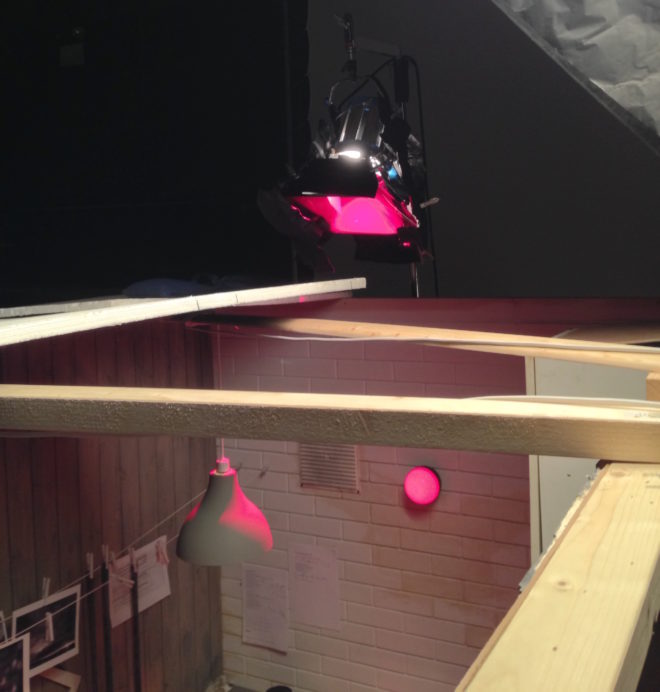

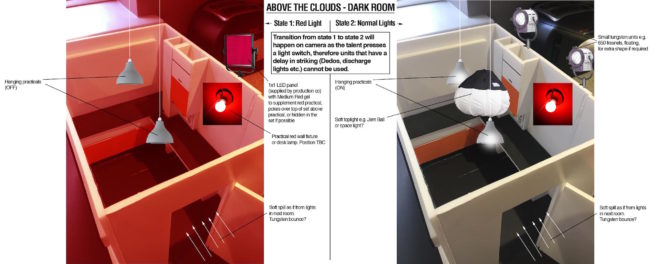

There have been many other examples of the beauty/realism problem throughout my career. One that springs to mind is Above the Clouds, where the 2.5K HMI which I was using as a backlight for a night exterior was in an unrealistic position. The ground behind the action sloped downwards, so the HMI on its wind-up stand threw shafts of light upwards. With the money for a cherry-picker, a far more moon-like high-angle could have been achieved. Without such funds, my only alternative was to sacrifice the beauty of a backlight altogether, which I was not willing to do.

The difference between that example and Annabel Lee is that Clouds director Leon Chambers was unable to accept the unrealistic lighting, and ended up cutting around it. So I think it’s quite important to get on the same page as your director when you’re lighting with limited means.

I remember asking Paul Hyett when we were prepping Heretiks, “How do you feel about shafts of ‘sunlight’ coming into a room from two different directions?” He replied that “two different directions is fine, but not three.” That was a very nice, clear drawing of the line between beauty (or at least stylisation) and realism, which helped me enormously during production.

The beauty/realism/cost triangle is one we all have to navigate. Although it might sometimes give us regrets about what could have been, as long we’re on the same page as our directors we should still get results we can all live with.

Cinematic Lighting consists of four hour-long modules: Day Exterior, Day Interior, Night Interior and Night Exterior. Each module follows the blocking, lighting and shooting of a short scripted scene (inspired by the fantasy web series

Cinematic Lighting consists of four hour-long modules: Day Exterior, Day Interior, Night Interior and Night Exterior. Each module follows the blocking, lighting and shooting of a short scripted scene (inspired by the fantasy web series

Forests typically have no artificial illumination, except perhaps practical torches carried by the cast. This means that the DP will primarily be simulating moonlight.

Forests typically have no artificial illumination, except perhaps practical torches carried by the cast. This means that the DP will primarily be simulating moonlight.

After that, I sat down over coffee with Ben Millar, my gaffer. We analysed the footage from principal photography and reverse-engineered the lighting. I say “we”; it was mostly Ben. This is why a DP hires a good gaffer!

After that, I sat down over coffee with Ben Millar, my gaffer. We analysed the footage from principal photography and reverse-engineered the lighting. I say “we”; it was mostly Ben. This is why a DP hires a good gaffer!