Shooting on one camera, getting the lighting and framing perfect for just one angle at a time, used to be a hallmark of quality in film and television. Nowadays many drama DPs are expected to achieve comparable quality while photographing two or more angles simultaneously, with all the attendant problems of framing out booms, lights and other cameras.

So what is the best way to tackle multi-camera shooting? Let’s consider a few approaches.

1. Two sizes

The most straightforward use of a B camera is to put it close to the A camera and point it in the same direction, just with a different lens. One disadvantage is that you’re sacrificing the ability to massage the lighting for the closer shot, perhaps bringing in a bounce board or diffusion frame that would flatter the actor a little more, but which would encroach on the wider frame.

Another limitation is that the talent’s eye-line will necessarily be further off axis on one of the shots. Typically this will be the wider camera, perhaps on a mid-shot including the shoulder of the foreground actor, while the other camera is tighter in terms of both framing and eye-line, lensing a close-up through the gap between the shoulder and the first camera.

The sound department must also be considered, especially if one camera is very wide and another is tight. Can the boom get close enough to capture the kind of close-miked audio required for the tight shot without entering the wide frame?

Some TV series are solving this problem by routinely painting out the boom in the wider shots. This is usually easy enough in a lock-off, but camera movement will complicate things. It’s an approach that needs to be signed off by all the major players beforehand, otherwise you’re going to get some panicked calls from a producer viewing the dailies.

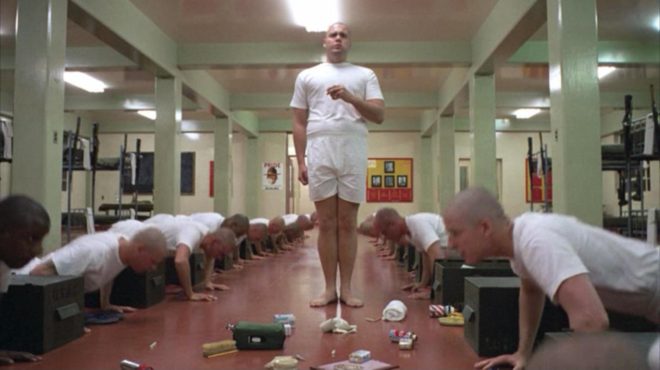

2. Cross-shooting

This means filming a shot-reverse simultaneously: over character A’s shoulder onto character B, and over character B’s shoulder onto character A. This approach is an editor’s delight because there is no danger that the performance energies will be different when they cut from one person to the other, nor that arm or head positions will throw up continuity errors.

Keeping the cameras out of each other’s frames is of course an issue, one usually handled by backing them off and choosing tighter lenses. (Long lenses are an unavoidable side effect of multi-camera cinematography.) Two booms are required, and keeping their shadows out is four times as difficult.

Lighting can take twice as long too, since you now have two cast members who need to look their best, and you need to maintain mood, shape and contrast in the light in both directions simultaneously. Softer and toppier light is usually called for.

The performances in certain types of scene – comedy with a degree of improvisation, for example – really benefit from cross-shooting, but it’s by far the most technically challenging approach.

3. Inserts

Grabbing inserts, like close-ups of people’s hands dealing with props, is a quick and simple way of getting some use out of a second camera. Lighting on such shots is often not so critical, they don’t need to be close-miked, and it’s no hassle to shoot them at the same time as a two-shot or single.

There is a limit to how many inserts a scene needs though, so sooner or later you’ll have to find something else to do with the camera before the producer starts wondering what they’re paying all that extra money for.

4. Splinter unit

The idea of sending B camera off to get something completely separate from what A camera is doing can often appeal. This is fine for GVs (general views), establishing shots of the outside of buildings, cutaways of sunsets and so on, but anything much more complicated is really getting into the realm of a second unit.

Does the set or location in front of camera need to be dressed? Then someone from the art department needs to be present. Is it a pick-up of an actor? Well, then you’re talking about hair, make-up, costume, continuity, sound…

With the extra problems that a second camera throws up, it’s a fallacy to think it will always speed up your shoot; the opposite can easily happen. An experienced crew and a clear plan worked out by the director, DP, operators and gaffer is definitely required. However, when it’s done well, it’s a great way to increase your coverage and give your editor more options.

The first colour wheel was drawn by Sir Isaac Newton in 1704, and it’s a precursor of the CIE diagram we met last week. It’s a method of arranging hues so that useful relationships between them – like primaries and secondaries, and the schemes we’ll cover below – can be understood. As we know from last week, colour is in reality a linear spectrum which we humans perceive by deducing it from the amounts of light triggering our red, green and blue cones, but certain quirks of our visual system make a wheel in many ways a more useful arrangement of the colours than a linear spectrum.

The first colour wheel was drawn by Sir Isaac Newton in 1704, and it’s a precursor of the CIE diagram we met last week. It’s a method of arranging hues so that useful relationships between them – like primaries and secondaries, and the schemes we’ll cover below – can be understood. As we know from last week, colour is in reality a linear spectrum which we humans perceive by deducing it from the amounts of light triggering our red, green and blue cones, but certain quirks of our visual system make a wheel in many ways a more useful arrangement of the colours than a linear spectrum.