Virtual production has been on everyone’s lips in the film industry for a couple of years now, but like all new technology it didn’t just appear overnight. Let’s trace the incremental steps that brought us to the likes of The Mandalorian and beyond.

The major component of virtual production – shooting actors against a large LED screen displaying distant or non-existent locations – has its roots in the front- and rear-projection common throughout much of the 20th century. This involved a film projector throwing pre-recorded footage onto a screen behind the talent. It was used for driving scenes in countless movies from North by Northwest to Terminator 2: Judgment Day, though by the time of the latter most filmmakers preferred blue screen.

The problem with blue and green screens is that they reflect those colours onto the talent. If the screen is blue and the inserted background is clear sky that might be acceptable, but in most cases it requires careful lighting and post-production processing to eliminate the blue or green spill.

Wanting to replace these troublesome reflections with authentic ones, DP Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC conceived an “LED Box” for 2013’s Gravity. This was a 20’ cube made of LED screens displaying CG interiors of the spacecraft or Earth slowly rotating beneath the characters. “We were projecting light onto the actors’ faces that could have darkness on one side, light on another, a hot spot in the middle and different colours,” Lubezki told American Cinematographer. “It was always complex.” Gravity’s screens were of a low resolution by today’s standards, certainly not good enough to pass as real backgrounds on camera, so the full-quality CGI had to be rotoscoped in afterwards, but the lighting on the cast was authentic.

Around the same time Netflix’s House of Cards was doing something similar for its driving scenes, surrounding the vehicle with chromakey green but rigging LED screens just out of frame. The screens showed pre-filmed background plates of streets moving past, which created realistic reflections in the car’s bodywork and nuanced, dynamic light on the actors’ faces.

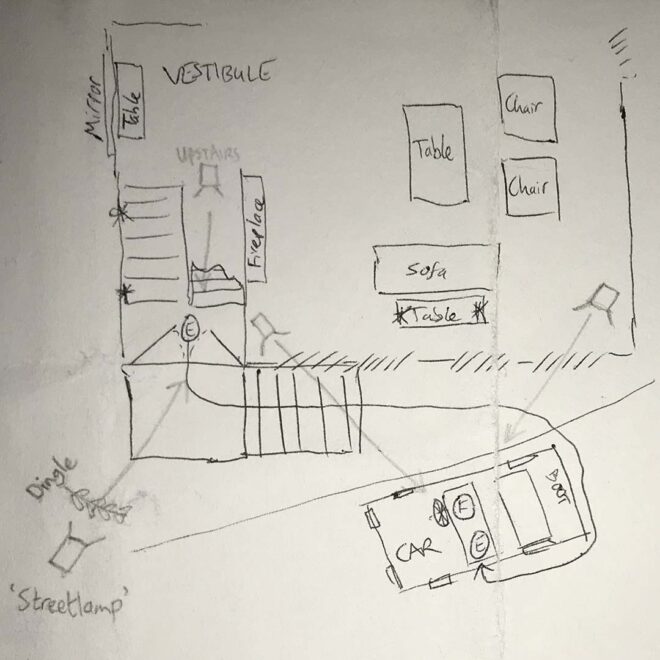

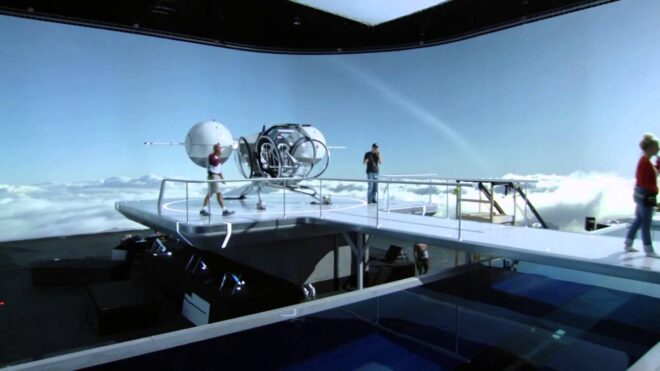

Also released in 2013 was the post-apocalyptic sci-fi Oblivion. Many scenes took place in the Sky Tower, a glass-walled outpost above the clouds. The set was surrounded by 500×42’ of white muslin onto which cloud and sky plates shot from atop a volcano were front-projected. Usually, projected images are not bright enough to reflect useful light onto the foreground, but by layering up 21 projectors DP Claudio Miranda, ASC was able to achieve a T1.3-2.0 split at ISO 800. Unlike those of Gravity’s low-rez LED Box, the backgrounds were also good enough to not need replacing in post.

It would take another few years for LED screens to reach that point.

By 2016 the technology was well established as a means of creating complex light sources. Deepwater Horizon, based on the true story of the Gulf of Mexico oil rig disaster, made use of a 42×24’ video wall comprising 252 LED panels. “Fire caused by burning oil is very red and has deep blacks,” DP Enrique Chediak, ASC explained to American Cinematographer, noting that propane fires generated by practical effects crews are more yellow. The solution was to light the cast with footage of genuine oil fires displayed on the LED screen.

Korean zombie movie Train to Busan used LED walls both for lighting and in-camera backgrounds zipping past the titular vehicle. Murder on the Orient Express would do the same the following year.

Meanwhile, on the set of Rogue One, vehicles were travelling a little bit faster; a huge curved screen of WinVision Air panels (with a 9mm pixel pitch, again blocky by today’s standards) displayed a hyperspace effect around spacecraft, providing both interactive lighting and in-camera VFX so long as the screen was well out of focus. The DP was Greig Fraser, ACS, ASC, whose journey into virtual production was about to coincide with that of actor/director/producer Jon Favreau.

Favreau had used LED screens for interactive lighting on The Jungle Book, then for 2018’s The Lion King he employed a virtual camera system driven by the gaming engine Unity. When work began on The Mandalorian another gaming engine, Unreal, allowed a major breakthrough: real-time rendered, photo-realistic CG backgrounds. “It’s the closest thing to playing God that a DP can ever do,” Fraser remarked to British Cinematographer last year. “You can move the sun wherever you want.”

Since then we’ve seen LED volumes used prominently in productions like The Midnight Sky, The Batman and now Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, with many more using them for the odd scene here and there. Who knows what the next breakthrough might be?