This is the first in a series of posts where I will look in detail at the four means of controlling the brightness of a digital video image: aperture, neutral density (ND) filters, shutter angle and ISO. It is not uncommon for newer cinematographers to have only a partial understanding of these topics, enough to get by in most situations; that was certainly the case with me for many years. The aim of this series is to give you an understanding of the underlying mechanics which will enable you to make more informed creative decisions.

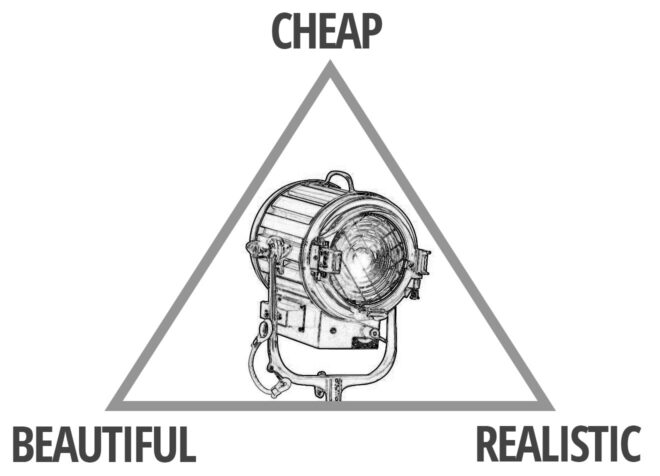

You can change any one of the four factors, or any combination of them, to reach your desired level of exposure. However, most of them will also affect the image in other ways; for example, aperture affects depth of field. One of the key responsibilities of the director of photography is to use each of the four factors not just to create the ideal exposure, but to make appropriate use of these “side effects” as well.

f-stops and t-stops

The most common way of altering exposure is to adjust the aperture, a.k.a. the iris, sometimes described as changing “the stop”. Just like the pupil in our eyes, the aperture of a photographic lens is a (roughly) circular opening which can be expanded or contracted to permit more or less light through to the sensor.

You will have seen a series of numbers like this printed on the sides of lenses:

1 1.4 2 2.8 4 5.6 8 11 16 22 32

These are ratios – ratios of the lens’ focal length to its iris diameter. So a 50mm lens with a 25mm diameter iris is at f/2. Other lengths of lens would have different iris diameters at f/2 (e.g. 10mm diameter for a 20mm lens) but they would all produce an image of the same brightness. That’s why we use f-stops to talk about iris rather than diameters.

But why not label a lens 1, 2, 3, 4…? Why 1, 1.2, 2, 2.8…? These magic numbers are f-stops. A lens set to f/1.4 will let in twice as much light as (or “one stop more than”) a lens set to f/2, which in turn will let in twice as much as one set to f/2.8, and so on. Conversely, a lens set to f/2.8 will let in half as much light as (or “one stop less than”) a lens set to f/2, and so on. (Note that a number between any of these f-stops, e.g. f/1.8, is properly called an f-number, but not an f-stop.) These doublings or halvings – technically known as a base-2 logarithmic scale – are a fundamental concept in exposure, and mimic our eyes’ response to light.

If you think back to high-school maths and the πr² squared formula for calculating the area of a circle from its radius, the reason for the seemingly random series of numbers will start to become clear. Letting in twice as much light requires twice as much area for those light rays to fall on, and remember that the f-number is the ratio of the focal length to the iris diameter, so you can see how square roots are going to get involved and why f-stops aren’t just plain old round numbers.

If you’re shooting with a cine lens, rather than a stills lens, you’ll see the same series of numbers on the barrel, but here they are T-stops rather than f-stops. T-stops are f-stops adjusted to compensate for the light transmission efficiency. Two different lenses set to, say, f/2 will not necessarily produce equally bright images, because some percentage of light travelling through the elements will always be lost, and that percentage will vary depending on the quality of the glass and the number of elements. A lens with 100% light transmission would have the same f-number and T-number, but in practice the T-number will always be a little bigger than the f-number. For example, Cooke’s 15-40mm zoom is rated at a maximum aperture of T2 or f/1.84.

Fast and slow lenses

When buying or renting a lens, one of the first things you will want to know is its maximum aperture. Lenses are often described as being fast (larger maximum aperture, denoted by a smaller f- or T-number like T1.4) or slow (smaller maximum aperture, denoted by a bigger f- or T-number like T4). These terms come from the fact that the shutter speed would need to be faster or slower to capture the same amount of light… but more on that later in the series.

Faster lenses are generally more expensive, but that expense may well be outweighed by the savings made on lighting equipment. Let’s take a simple example, and imagine an interview lit by a 4-bank Kino Flo and exposed at T2.8. If our lens can open one stop wider (known as stopping up) to T2 then we double the amount of light reaching the sensor. We can therefore halve the level of light – by turning off two of the Kino Flo’s tubes or by renting a cheaper 2-bank unit in the first place. If we can stop up further, to T1.4, then we only need one Kino tube to achieve the same exposure.

Side effects

One of the first things that budding cinematographers learn is that wider apertures make for a smaller depth of field, i.e. the range of distances within which a subject will be in focus is smaller. In simple terms, the background of the image is blurrier when the depth of field is shallower.

It is often tempting to go for the shallowest possible depth of field, because it feels more cinematic and helps conceal shortcomings in the production design, but that is not the right look for every story. A DP will often choose a stop to shoot at based on the depth of field they desire. That choice of stop may affect the entire lighting budget; if you want to shoot at a very slow T14 like Douglas Slocombe did for the Indiana Jones trilogy, you’re going to need several trucks full of lights!

There is another side effect of adjusting the aperture which is less obvious. Lenses are manufactured to perform best in the middle of their iris range. If you open a lens up to its maximum aperture or close it down to its minimum, the image will soften a little. Therefore another advantage of faster lenses is the ability to get further away from their maximum aperture (and poorest image quality) with the same amount of light.

Finally it is worth noting that the appearance of bokeh (out of focus areas) and lens flares also changes with aperture. The Cooke S4 range, for example, renders out-of-focus highlights as circles when wide open, but as octagons when stopped down. With all lenses, the star pattern seen around bright light sources will be stronger when the aperture is smaller. You should shoot tests – like these I conducted in 2017 – if these image artefacts are a critical part of your film’s look.

Next time we’ll look at how we can use ND filters to control exposure without compromising our choice of stop.

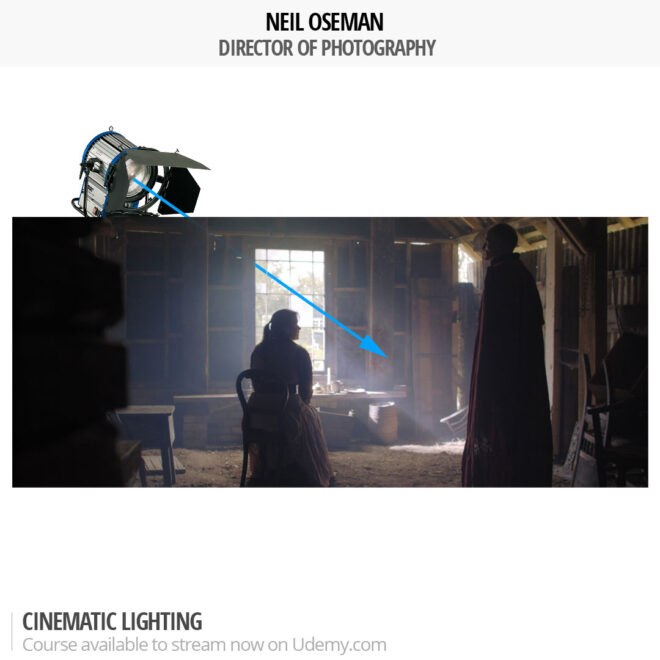

Learn how to use exposure practically with my Cinematic Lighting online couse. Enter voucher code INSTA90 for an amazing 90% off.