So far, this blog series about my cinematography of The Little Mermaid has covered the biggest and most complex scenes in the movie. Today I’m going to look at some smaller scenes, and how I employed the cinematography tenet of lighting from the back to quickly build a look for these which has depth, mood and drama.

Many of these examples are specifically cross-backlighting, something I covered in my Lighting Techniques series, but I’ll quickly recap since it has so much relevance here. It involves lighting two characters facing each other with two sources, on the far side of the eye-line (short key), crossed so that each source keys one character and often backlights the other too.

So with that in mind, let’s proceed to the examples from my shooting diary.

Day 1

The first week is pretty much all in houses with just a few principals, so an easy start. Day 1’s schedule is tight though. We start in a third floor bedroom – no way lamps are getting up to those windows from outside, so I’m relying on natural light augmented with a bit of cross-backlight cheated inside the room. (There’s a Kino Flo shining at Elle over Cam’s right shoulder, for example.) Once the haze is in it looks great. After we get the main coverage, we head out to the garden for the next scene, while the ‘B’ camera team steps in to pick up a couple of inserts…

Day 3

…It’s a night scene and the grips have tented the window. To get a nice blue glow coming in, I have two 4×4 Kino Flos set either side of the window (outside), and they give a great wrapping backlight to the actors and the set dressing. Smoke and a cool white balance of 3,200K (the Kinos are tubed for 5,600K) complete the look. It owes a lot to a scene from Hook, one of Blake’s (director Blake Harris) reference movies which I watched during preprod. This stuff definitely filters in and inspires things!

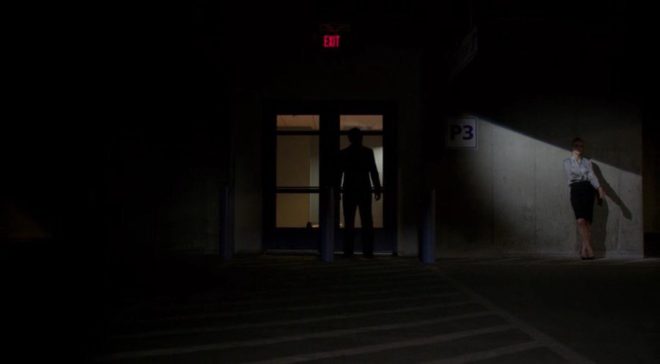

Day 13

Our first day on stage. It’s weird to be back at the former supermarket I spent five weeks of preproduction in. The first set, Locke’s chamber, is very confined and the walls don’t wild, so it’s quite slow-going to work in there. We fire a 5K fresnel through the stained glass window at the back of the set. Then I fall back on the tried and tested method of cross-backlighting even though I know that it will be hard to hide the lamps (a 650W fresnel in both of the upper rear corners of the set) from camera. In the end I have the art department dress drapes in front of them. For the villain’s single I leave the light hard, but for the hero’s single we use bounce boards to wrap the light around his face more…

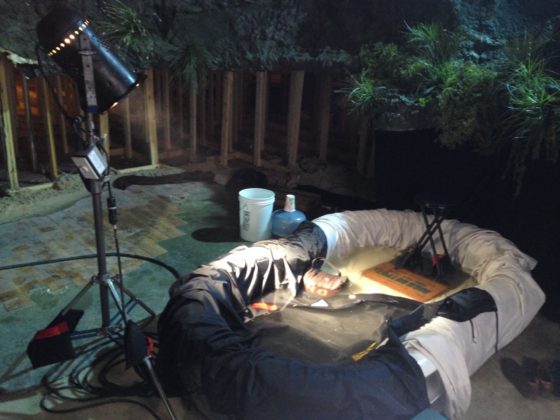

Day 28

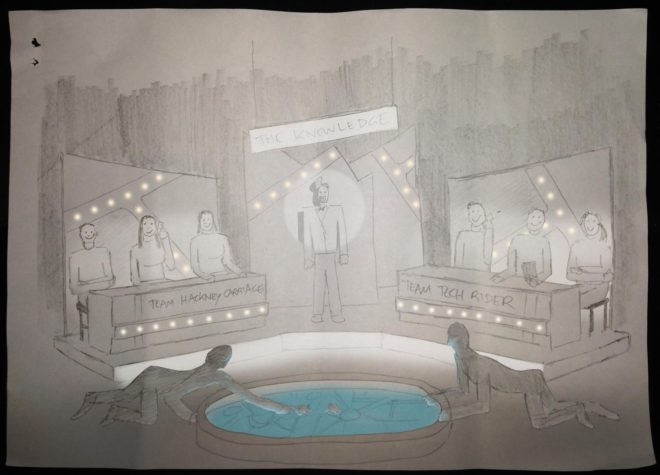

We start with the fortune-teller’s tent, another small set constructed on stage. In fact, it’s just an Easy-Up artfully draped with fabrics. Initially there’s nowhere to get light in from except the front, but I know that this will leave the scene looking flat and fake, so I work with the art department again to make holes in the top rear corners. Through those we shine tungsten-bubbled “Fat Boy” Kino Flos. (These 2ft 4-bank units are giving the dual kickers on Cam in the centre, and the beautiful down-light on the background fabrics, bringing out the ruching. Each one also provides a little key-light on the two ladies.) The other sources are “moonlight” coming in through the entrance, linking us to the circus exteriors, and a stylised slash of light across Thora’s eyes from a Source Four, suggested by Jason (key grip Jason Batey). Adding foreground practicals is an important final touch to expand the depth and scale of the set…

Day 31

It’s the last day of principal photography. Our big scene of the day is the newspaper office where Cam works, which is a set in the front of the studio, using the building’s real windows. We fire the 12K in and gel it with half CTS for a nice morning sunlight effect. We’re shooting towards the windows, which have blinds, so we get some nice shafts of light, though sometimes it’s a little too smokey. Running haze is a pretty skilled and tricky job, and involves considering the lens length and backlight, which both affect how much the smoke shows up on camera. When we get it right, combined with the dark wood period furniture, it totally sells the 1937 setting. Apparently people at video village are loving it, saying it looks like Mad Men….

Next week, in the final part of my blog series on The Little Mermaid, I’ll share my experiences of shooting the sunset denouement while up to my waist in the Atlantic Ocean.